INTRODUCTION

In the landmark 2024 Ontario Court of Appeal case Pinnacle International (One Yonge) Ltd. v. Torstar Corporation (2024 ONCA 755), the Court addressed several important issues regarding contractual rights in lease and sublease agreements.

This case provides important guidance for understanding commercial real estate leases, particularly with respect the extent to which the factual matrix should be considered when examining leases and subleases, the importance of defining key terms when drafting contracts, and the applicability of the Limitations Act and the Real Property Limitations Act.

Clarity in Drafting

In commercial real estate leases, it is crucial to define key terms and concepts with precision to avoid ambiguity regarding their meaning. In this case, ambiguity over the terms “profit” and “reasonable costs” were key to the dispute.

The Court’s ruling demonstrates that parties should be crystal clear in the lease agreement about which party benefits from these profits, the timing of such benefits (e.g., throughout the entire lease term, including or excluding applicable fixturing periods), and the specific inclusions or exclusions in the calculation of net profits.

The Importance of the Factual Matrix

The Court reiterated that, when interpreting leases (or other commercial contracts), it is critical to examine the factual background known to the parties at the time the contract was formed. This goes beyond a purely textual analysis and ensures that contractual interpretation reflects the actual circumstances surrounding the contract’s drafting and execution. In this case, the majority emphasized that the factual matrix—including the knowledge that the third-floor open-air space was unusable—was crucial in interpreting the lease provisions.

Applicable Limitation Period

Another important aspect of this case was the application of the appropriate limitation period for claims under the lease. Payments arising from a lease that are not strictly considered “rent” (even if the contract defines them as such) may be governed by the two-year limitation period under the Limitations Act, as opposed to the six-year period under the Real Property Limitations Act. This decision highlighted the risk that, even when payments are labeled as “rent,” courts may classify them differently, affecting the applicable limitation period.

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE CASE

Torstar Corporation (“Torstar”) occupied the commercial building at 1 Yonge Street from 1971 to 2022 under a lease agreement with Pinnacle International (One Yonge) Ltd. (“Pinnacle”). The lease required Torstar to pay Pinnacle net “profit” earned from any sublease. The key issue in this case was determining what constituted “profit.”

The building consists of two connected sections: (1) a 25-storey office tower and (2) a six-storey “Podium,” including a three-storey open-space warehouse. The third floor of the warehouse, which was central to the dispute, included both a usable office space (46,707 sq. ft.) and an open-air space (18,827 sq. ft.).

Article 8.1 of the lease permitted Torstar to sublet the space, but any profit from subletting—after deducting “reasonable costs”—was to be passed on to Pinnacle as additional rent.

In July 2011, Torstar entered into a sublease with College Boreal, which terminated in August 2020. The sublease specified a rentable area of approximately 46,707 sq. ft. for the third-floor office space, excluding the open-air portion of the warehouse. However, Torstar continued paying rent on the entire 65,534 sq. ft. of the third floor, including the open-air space, which neither Torstar nor Boreal could use.

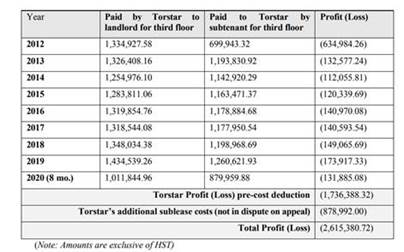

Despite Torstar incurring a $2.6 million loss on the sublet premises, Pinnacle alleged that Torstar had profited from the sublease and sought to recover $1.1 million in profit.

This claim was based on the fact that Torstar charged Boreal more per square foot for the usable portion of the space than what was stipulated in the original lease. However, Torstar provided the following chart in its materials, which demonstrates that the total rent Torstar paid to Pinnacle for the entire third floor was always greater than the total rent Torstar received from Boreal. The chart outlines the gross rent (Basic plus Additional Rent) Torstar paid to Pinnacle for the third floor of the building during the Boreal sublease period. The gross rent ranged from $19.15 to $21.89 per square foot, paid on 65,534 square feet, including the third-floor Open Air Space. It also shows the gross rent Boreal paid Torstar, which ranged from $24.91 to $26.99 per square foot, paid on the 46,707 square feet of usable third-floor space.

The motion judge ruled in favor of Pinnacle, requiring Torstar to pay the $1.1 million. The judge held that article 8.1 of the lease did not allow Torstar to deduct the full rent it paid for the third floor as a “reasonable cost” in determining whether it had profited from the sublease.

The decision was subsequently appealed, with the Ontario Court of Appeal addressing two main issues:

- Whether the third-floor open-air space could be included as a reasonable cost deductible from profit in the lease.

- Which limitation period applied to the claim for net profits.

THE ONTARIO COURT OF APPEAL’S DECISION

The Court allowed Torstar’s appeal, ruling in favor of the tenant. The Court accepted that the third-floor open-air space was part of the sublease rented to College Boreal and should be included as a reasonable cost deductible from profit under article 8.1 of the lease.

The majority identified three major errors in the motion judge’s decision:

- The Factual Matrix: The majority emphasized that when interpreting the lease, courts must look beyond the bare text to consider the factual background known to the parties. When Torstar and Boreal entered into the sublease, it was clear that the third-floor open-air space was inaccessible, and neither Torstar nor Boreal could use it. Despite this, Torstar was obligated to pay rent for the entire third floor. It would not have made commercial sense for Torstar to sublet only the usable portion of the third floor.

- The Sublease as a Whole: The majority held that the motion judge erred in not considering the sublease in its entirety. Viewed in light of the factual matrix, the sublease applied to the entire third floor, and the rent should have been calculated based on the usable portion.

- Commercial Absurdity: Excluding the full rent paid for the third floor from the calculation of profit created a commercial absurdity. Requiring Torstar to pay Pinnacle $1.1 million when Torstar had incurred a $2.6 million loss on the sublease was unreasonable. The majority maintained that “profit” should be understood in its ordinary and grammatical sense as “the excess of returns over expenditure.”

Additionally, the majority ruled that the Limitations Act applied to the claim for net profit under Article 8.1, overturning the motion judge’s decision.

In Ontario, two primary statutes govern limitation periods: the Limitations Act and the Real Property Limitations Act. The Limitations Act provides general timeframes for most claims, while the Real Property Limitations Act sets specific periods for real property matters.

The Limitations Act has a basic two-year limitation period, starting from the day the claimant discovered, or should have discovered, the claim. An ultimate limitation period of 15 years also applies, regardless of when the claim was discovered.

On the other hand, the Real Property Limitations Act has a six-year limitation period for arrears of rent. However, this does not apply in all cases, such as when there is an action for redemption by a mortgagor or claims involving prior mortgagees in possession of land.

In this case, the claim was “not based on an obligation to pay rent” as defined in the Real Property Limitations Act but for a breach of a lease term. Therefore, the majority determined the two-year limitation period under the Limitations Act should apply, as Torstar was required to pay Pinnacle net “profit,” not rent.

CONCLUSION

In Pinnacle International (One Yonge) Ltd. v. Torstar Corporation, the Ontario Court of Appeal reinforced the significance of clear contract drafting, the role of the factual matrix in interpretation, and the importance of understanding limitation periods in lease disputes. The case serves as a cautionary tale for landlords, tenants, and parties to a sublease to carefully define terms and anticipate potential conflicts, ensuring that commercial agreements reflect the actual circumstances and intentions of the parties involved.

This article is provided for general information purposes and should not be considered a legal opinion. Clients are advised to obtain legal advice on their specific situations.

If you have questions, please reach out

Mississauga Head Office

3 Robert Speck Parkway, Suite 900

Mississauga, ON L4Z 2G5

Tel: 905.276.9111

Fax: 905.276.2298

Burlington

3115 Harvester Rd., Suite 400

Burlington, ON L7N 3N8

Privacy Policy | Accessibility Policy | © 2025 Keyser Mason Ball, LLP All Rights Reserved.